On 16 September, the European Parliament adopted my report on cross-border cooperation between tax authorities in Europe. It is the first ever implementation report of the European Parliament in the area of economic and monetary policy. The conclusion: since the first directive in 2011, an increasing amount of tax-related data has been exchanged between Member States. That is great progress. At the same time, there is a lack of implementation: there are considerable doubts about the effectiveness and completeness of the exchange of tax-relevant data across national borders. Here, a broad pro-European majority in the Parliament called on the Member States and the Commission to commit to significant improvements. The final report was adopted with 561 votes in favour, 12 against and 116 abstentions. The full report is available here.

As rapporteur, I was responsible for drafting a common parliamentary position. More than a year and a half has passed since my team and I began our research for the implementation report. During this time, we have pushed in vain for the Council and the Commission to give Parliament access to the information needed to review the implementation of the Directive in the Member States. This is despite the fact that, according to the European Treaties, the European Parliament has the right and the responsibility to control the Commission in its work. So we had to base our work on the limited information publicly available and a number of studies. A report by the European Court of Auditors provided valuable insights, as did a study commissioned by the European Parliament’s Research Service on this occasion. Also thanks to information from whistleblowers, we were able to get a better understanding of the state of tax cooperation in Europe. Due to the lack of access to documents, this evaluation can however only be preliminary. In particular, the member states and the European Commission have refused any access to the tax information exchange data shared annually by each member state with the Commission and all other member states. I will make sure that the Parliament fights with all legal means for access to those data. In the meanwhile I would appreciate access to the information by any anonymous source ;-).

‘Report on the implementation of EU requirements for the exchange of tax information: Progress, lessons learned and obstacles to be overcome’

1. Findings

1.1 Progress

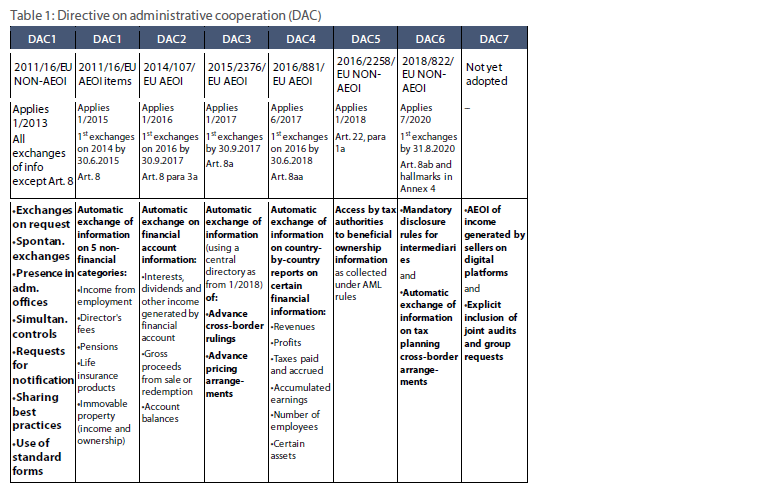

Unlike 15 years ago, tax-relevant data is now exchanged between Member States automatically. For example, data on income and assets in simply structured bank accounts and custodial accounts flow automatically between Member States. Although this progress has been written into European law, it was achieved mainly thanks to pressure from the USA, the G20 and the OECD, as well as after scandals such as LuxLeaks and the PanamaPapers. Unfortunately, Member States only have to exchange data which is easily available to their own authorities. There is no obligation to make further data available in order to share it with other Member States. The Directive and its six extensions so far cover the following tax-relevant information, albeit with loopholes: Income from employment, directors’ fees, pensions, life insurance products, and immovable property (DAC 1); financial accounts and related income (DAC 2); tax rulings and advance pricing arrangements (DAC 3); non-public country-by-country tax reporting by large companies (DAC 4); tax authorities’ access to beneficial ownership information collected under anti-money laundering rules (DAC 5); cross-border arrangements for tax planning purposes (e.g. acquisition of a loss-making business or operations allowing for the reclassification of income into a category taxed at a lower rate) and mandatory disclosure rules for intermediaries (lawyers, consultants and accountants as well as banks, trustees, insurance companies, financial advisors and other service providers) (DAC 6); revenues generated by sellers on digital platforms (DAC 7). The EU Commission is currently working on DAC8 which is to cover crypto assets. My report covers the effective implementation of DAC1, DAC2, DAC3 and DAC4.

Source: EPRS 2021, p. 7. DAC7 has since been adopted.

1.2 Shortcomings

1.2.1 Quantitative findings on the effective implementation of tax cooperation

While very little quantitative information is available from European sources, international reviews conducted by the OECD Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes (short OECD Global Forum) and the Financial Action Task Force document the extent of the shortcomings in the Member States.

Results of OECD Global Forum Peer Review on Automatic Exchange of Information

10 Member States have not fully implemented the rules for the automatic exchange of tax information in the EU, namely Belgium, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Germany, Hungary, Latvia, the Netherlands, Poland and the Slovak Republic. Romania does not even have the legal framework in place for the automatic exchange of information. Unfortunately, a majority of Christian Democrats, Liberals and far right have ensured the deletion of the explicit criticism of Romania in my report.

Results of OECD Global Forum Peer Review on Exchange of Information upon Request

In addition to the automatic exchange of information between Member States, there is also a standard for the Exchange of Information upon Request (EOIR). Here, the international review by the OECD Global Forum also revealed shortcomings in many EU Member States: In summary, material deficiencies have been identified in 18 Member States. Malta even received an overall ‘partially compliant’ score in the peer review by the Global Forum for EOIR, meaning the EOIR standard is only partly implemented. No material deficiencies were identified in only eight Member States: Estonia, Italy, Finland, Lithuania, France, Slovenia, Sweden and Ireland.

Detailed findings:

- 19 Member States are not fully compliant on ‘ownership and identity information’: Estonia, Austria, Hungary, Belgium, Luxembourg, Bulgaria, Croatia, Netherlands, Cyprus, Poland, Czechia, Portugal, Denmark, Romania, Slovakia, Greece, Germany, Malta and Spain.

- 6 Member States are not fully compliant on ‘accounting information’: Croatia, Cyprus, Greece, Slovakia, Spain and Malta.

- 5 Member States are not fully compliant on ‘banking information’ Hungary, Malta, Netherlands, Denmark and Slovakia.

- 7 Member States are not fully compliant on ‘access to information’: Austria, Hungary, Belgium, Latvia, Czechia, Portugal and Slovakia.

- 3 Member States are not fully compliant on ‘rights and safeguards’ for ease of access to information: Hungary, Belgium and Luxembourg.

- 5 Member States are not fully compliant on ‘EOI mechanisms’: Austria, Latvia, Cyprus, Czechia and Portugal.

- 3 Member States are not fully compliant on ‘confidentiality’: Belgium, Latvia and Hungary.

- 3 Member States are not fully compliant on ‘rights and safeguards’ for the practice of information exchange: Hungary, Latvia and Czechia.

- 9 Member States are not fully compliant on ‘quality and timeliness of responses’: Italy, Malta, France, Luxembourg, Bulgaria; Portugal, Romania, Greece and Germany.

List adapted from EPRS 2021, p. 27, based on OECD Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes findings.

Financial Action Task Force: Effectiveness Rating of the Anti-Money Laundering measures in place

The international review of the measures taken by Member States to prevent money laundering and terrorist financing (AML/CFT) is even more damning: Of the 18 Member States reviewed, none of them received a rating indicating a high level of effectiveness. This indicates a clear lack of effective implementation of the measures which are not only needed to prevent financial crime, but which provide the basis for effective cooperation in tax matters as well.

The FATF rating looks at dimensions such as domestically coordinated actions on AML/CFT, international cooperation, appropriate supervision, preventive action taken by financial institutions (for example whether banks diligently check the identity of their prospective customers), confiscation of proceeds from financial crime etc. In total, the FATF looks at 11 dimensions to determine whether states fight money laundering effectively.

A summary of the FATF Effectiveness Ratings which we compiled for the sake of this report can be found here: https://sven-giegold.de/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/FATF_AMLCFT-Effectiveness-Ratings_EU-summary.pdf

1.2.2 Qualitative assessments

There is still too little information exchanged on certain types of income and assets. Only if all tax-related information is automatically exchanged across borders Member States can tax all income and assets earned or held by their citizens across borders equally. The existing directives have brought us closer to this goal. But notably real estate, trusts, shares in companies below the 25%+ ownership threshold, certain forms of capital gains and crypto assets are not yet part of the automatic exchange of information. Non-financial assets such as cash, art, gold or other valuables held in free ports, customs warehouses or safe deposit boxes, as well as the ownership of yachts and private jets, also do not have to be reported across borders so far.

Too little use is made of the information exchanged. It is of little effect if more and more information is exchanged while the data exchanged is underused. Our research reveals a lack of trained staff and effective IT infrastructure. There is also a lack of data to assess the reasons behind this lack of capacity. Which information received was used, which was not? And for what reason? The effectiveness of data exchanged for tax purposes is structurally non-auditable. There is much need for improvement here.

There is a lack of control regarding the quality of the tax information exchanged. So far, only a few Member States check the quality of the data they exchange. This fact significantly increases the risk that the reported data is incomplete or inaccurate. The lack of quality controls is all the more worrying in view of the fact that few Member States check the accuracy of the information they themselves have received from financial institutions. However, experience shows that not all financial market participants can be trusted to comply with regulations, even if others put in a lot of effort and commitment.

Existing European rules have been poorly implemented. The effectiveness and completeness of the tax information exchanged depends on the accuracy of the information on beneficial owners collected under anti-money laundering rules. But this is precisely where the problem lies. The incorrect transposition and lack of effective enforcement of the anti-money laundering directives and the remaining weaknesses in the anti-money laundering framework undermine the effectiveness of the exchange of information. There are currently 11 infringement proceedings against Member States for the incorrect transposition of the fourth anti-money laundering directive and 16 (!) infringement proceedings because of the incorrect transposition of the fifth directive against money laundering and terrorist financing. And this is unfortunately only the tip of the iceberg, because many glaring deficiencies continue to be tolerated by the Commission. For example, Germany has a transparency register which is much worse than the one in Luxembourg, making an #OpenGermany analogous to the #OpenLux revelations impossible. These failures have a direct impact on the effectiveness of tax cooperation. Also, the data in the transparency registers is often outdated and incomplete.

Different standards lead to avoidable bureaucracy. In addition to the EU and OECD standards, reporting financial institutions must also comply with deviating rules from the US (“FATCA”). This leads to unnecessary bureaucracy. Likewise, varying threshold values do not make the collection of data any easier.

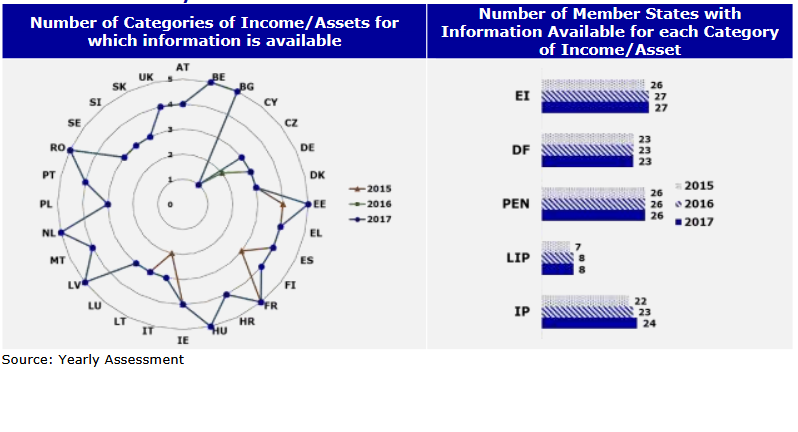

2. Proposals for improvement

Member States must exchange all types of income and assets currently covered by the Directive. So far, Member States are not obliged to do so. This means that although six categories of income and assets are covered by the Directive (e.g. income from employment and pension benefits), nine Member States only shared information on three of the six categories in 2017. This needs to change.

Source: European Commission 2019, p. 10. Availability of DAC1 Information.

The directive must be extended to the assets mentioned above (yachts, crypto, etc.), again combined with the obligation to also exchange them consistently. This applies especially to automatic access to information when EU citizens acquire real estate and company shares abroad.

Member States must commit to actively provide high-quality information. This means that Member States must work on the quality and availability of data and cannot just rely on existing data. The EU Commission must be proactive with on-site visits. Actors obliged to report information need easy access to an EU verification system for tax identification numbers (TINs).

Member States must consistently check the information provided by financial institutions and impose penalties where information is false. To this end, a uniform catalogue of measures is needed to standardise sanctions across the EU. The work of financial institutions and state inspectors can be facilitated by a Europe-wide verification mechanism for tax identification numbers (TINs). If the bank can immediately check a person’s tax number, this will put a stop to misinformation.

Beneficial owners need to be consistently recorded in order to ensure that the exchanged information can really be attributed to the actual owners and their correct member state of residence. So far, far too often only the legal owners are recorded, which can also be a lawyer who manages a fund on behalf of a wealthy family. But this is not good enough, because the fund must be attributed to the family – they are the beneficial owners who can dispose of the assets and the revenues.

Company shares below the 25%+ threshold also have to be reported. Under the current rules, four or more family members can own a company without this highly tax-relevant information being recorded, let alone exchanged. Reporting without a threshold is also reducing bureaucracy.

We need a review of the reporting requirements for financial institutions and other asset managers to see whether they should be extended. The same applies to the disclosure of tax benefits for individual companies, so-called “tax rulings”, for which there are still gaps in the exchange. The recent #LuxLetters scandal underlined the importance of this proposal, which is why we tabled additional plenary amendments to adequately reflect the findings of the investigative journalists.

Member States must be allowed to decide for themselves whether they want to use information obtained through the exchange of tax information for other law enforcement purposes. Combating crime should not need cross-border authorisation between EU states. Currently, the data exchanged may not even be used for all law enforcement purposes. The EU states from which the data was sent must explicitly authorise its use in individual cases, for example to fight money laundering and organised crime.

In order to be able to recover billions of euros in lost tax revenue, Member States must increase the capacities of their tax administrations. Research by the European Court of Auditors shows the importance of sophisticated IT systems that can effectively process large amounts of data and perform automated tasks. The European Union is already providing support for capacity building in the Member States. This support should be expanded and complemented by a European monitoring system. This system should record the amount of information exchanged per type of asset and income, as well as the additional tax revenue gained. However, this also means that the Member States must be much more transparent about the information they use, to what extent and with which results. The journey of tax-relevant information across Europe must be traceable. Here we propose that each data set be marked with an origin identifier of the country that provided the information. Our aim must be that the added-value of tax cooperation among European neighbours finally becomes visible and measurable.

The correct and comprehensive implementation of existing tax and anti-money laundering legislation is a prerequisite for the meaningful expansion of cooperation between tax authorities. It is the task of the European Commission to check the implementation and correct application of EU law and to take action where this is not the case. The Commission should fulfil this task consistently and initiate further infringement proceedings. In addition, the Commission should analyse the state of administrative cooperation between tax authorities every year and publish its findings. Then the European Parliament will no longer have to rely on information from international organisations to learn more about the state of tax cooperation in the European Member States. Member States must no longer hide behind a wall of missing information. European taxpayers and their representatives in the European Parliament have a right to know how well the tax authorities are working and to demand improvements.

Unify standards, abolish thresholds and exemptions. To reduce red tape, the EU should work within the OECD to harmonise US FATCA rules with EU and OECD standards (“CRS”) and to close loopholes and gaps. In Europe, we should remove all thresholds and exemptions. Simple and comprehensive rules are easier to implement and more effective than a system full of loopholes and thresholds. In the digital age, tax authorities can filter for themselves what data is of interest to them rather than asking obliged reporting entities to perform bureaucratic selections.

Initiate infringement proceedings immediately. The EU Commission has precise information from three sources on the inadequate implementation of EU law in the area of tax cooperation. The Global Forum of the OECD has documented deficiencies, as has the FATF. In addition, the Member States have reported directly to the EU Commission. Now the EU Commission must fulfil its mandate as guardian of the treaties and initiate infringement proceedings for the widespread lack of effective implementation.

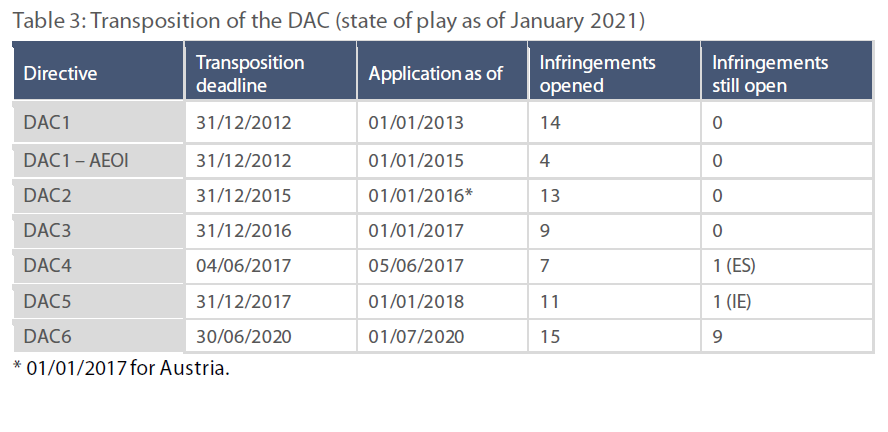

Source: EPRS 2021, p. 16. Note that this table only refers to transposition, not effective implementation of the Directive.

Sources:

ECORYS 2021, Report “Monitoring the amount of wealth hidden by individuals in international financial centres and impact of recent internationally agreed standards on tax transparency on the fight against tax evasion” https://op.europa.eu/de/publication-detail/-/publication/0f2b8b13-f65f-11eb-9037-01aa75ed71a1/language-en/format-PDF/source-223980111

European Commission 2018, “REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL on overview and assessment of the statistics and information on the automatic exchanges in the field of direct taxation” https://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/document/download/c2217f97-eeda-4fc9-9655-7bce9b06bc62_en

European Commission 2019, “Evaluation of Administrative Cooperation in Direct Taxation” Final Report https://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/document/download/5e5cdc23-4586-4115-96c5-0f8ee9ace506_en

European Court of Auditors 2021, Special Report 03/2021 “Exchanging tax information in the EU: solid foundation, cracks in the implementation” https://www.eca.europa.eu/en/Pages/DocItem.aspx?did=57680

European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS) 2021, “Implementation of the EU requirements for tax information exchange” https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/662603/EPRS_STU(2021)662603_EN.pdf

Financial Action Task Force (FATF) 2021, 4th Round Effectiveness Ratings http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/4th-Round-Ratings.xlsx

OECD Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes (OECD Global Forum) 2010-2021, Peer Reviews https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/taxation/global-forum-on-transparency-and-exchange-of-information-for-tax-purposes-peer-reviews_2219469x?_ga=2.61374444.131706240.1621422687-1265388792.1602508229

OECD Global Forum 2020, Malta: Peer Review Report on the Exchange of Information on Request (EOIR) https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/taxation/global-forum-on-transparency-and-exchange-of-information-for-tax-purposes-malta-2020-second-round_d92a4f90-en

OECD Global Forum 2020, Romania: Peer Review of the Automatic Exchange of Financial Account Information (AEOI) https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/9af6df81-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/9af6df81-en